| |

The

Story of Sculpture: From Clay to Bronze

| Introduction:

The Art of the Lost-Wax Process

The earliest known “lost-wax” castings date from the

early dynasties of Egypt, nearly 7,000 years ago, when metal was

poured into “investments” of fired clay that had been

shaped with the help of wax that was melted, or “lost”.

Then, sometime between 4,000 and 3,000 B.C., bronze was discovered,

probably by accident, as being a metal that was harder than copper

or tin alone. Thus began the era known as the Bronze Age.

Ancient “lost-wax” bronze castings have withstood the

centuries, visually telling the tale of past cultures, their religions,

and their social structures. For example, Chinese bronzes depicted

ceremonial images; Indian and Egyptian castings symbolized deities;

Africans cast images of nature; and the Greeks recreated the human

form.

|

|

|

|

Many of these cultures have since grown obsolete, their religions

have evolved and societies have changed. Elements of the “lost-wax”

process have been refined. Yet today, bronze casting is essentially

the same as it was in 2,000 B.C. during the Akkadian period.

Bronze is an alloy of 95% copper, 4% silicon and 1% manganese with

traces of other elements such as iron. Silicon bronze has been the

bronze of choice for fine art castings since its development in

the 1920s. It is corrosion-resistant, strong, resilient, formable

and weldable. Also known as "hot-cast" bronze, a fine

art "lost-wax" casting of silicon bronze is created through

many labor-intensive steps.

|

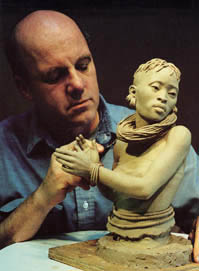

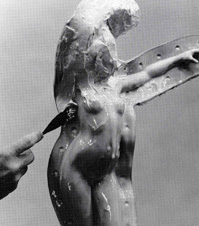

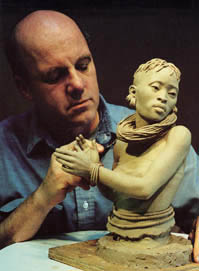

Sculptor

Tuck Langland works on

the clay for his sculpture "Kenyan Dancer". |

|

1.

Making the Original Clay Sculpture

To begin the process of making a bronze sculpture, most

sculptors choose to make an original out of clay. There are multitudes

of different clays available for the sculptor. The three main categories

of clay used for sculpture are water-based clay, oil-based clay,

and self-hardening/low-fire clay. Choosing the proper clay for a

particular project may simply be a matter of preference. Experience,

however, is perhaps the best teacher when deciding what type of

clay to use.

Most of the artists with Sculptureworks prefer to work with oil-based

clay (also known as plasticene, plastilene, or plastilina). The

main reason for working with oil-based clay is because it never

dries or hardens. It can always be softened and reworked if a change

needs to be made. The main concern with using oil-based clay is

how to have the clay soft enough to build the sculpture rapidly

and yet at the same time have the clay hard enough to produce good

detail. The usual solution is to choose a clay that is hard enough

for detail work and then just use heat to soften the clay for buildup.

Very

small sculptures are often modeled directly in wax which, though

more difficult to model, allows for maximum detail.

|

| 2.

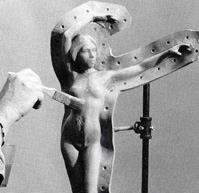

The Use of Armatures

An armature in a sculpture is a material used for supporting

the weight of the clay. An armature is usually necessary when portraying

a figure in motion or in a standing posture. The armature serves

as the underlying support to the sculpture. In some cases, a skeletal

formation can be made out of wire, or other materials such as pipe

or aluminum, that will help hold the clay in place, so that the

clay can be worked and detailed.

When working with large sculptures, weight is an important issue.

Thus, after the initial armature is constructed, sculptors often

use “fillers” such as styrofoam or aluminum foil to

“fill out” the form and reduce the amount of clay being

used. If most of the mass of the armature can be made with filler,

then the clay on top will be just a thin skin instead of a huge

thick mass that risks falling off.

Once the armature is built, the clay sculpture can then be formed

around and on the armature. The armature holds the parts of the

sculpture in place, allowing the sculptor the freedom to move the

clay along the armature to get the form that he or she wants.

For bas reliefs, an armature can be constructed which consists of

a grid of screws connected with wires to prevent the clay from sliding.

|

|

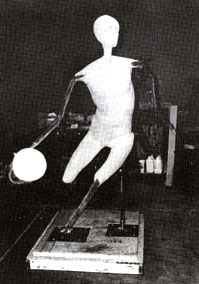

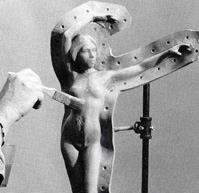

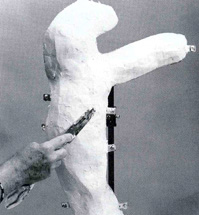

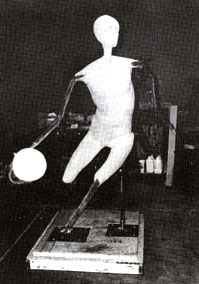

Sculptor

Blair Buswell made this

larger-than-life armature to support his monumental sculpture of basketball

legend Oscar Robertson. Blair covered this steel armature with foam

before adding the clay. |

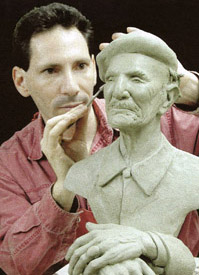

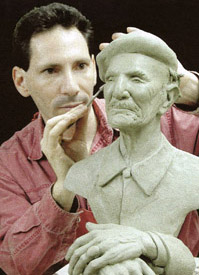

Sculptor

Paul Oestreicher

makes finishing touches to the clay version of his sculpture of painter

Alfred Levitt. |

|

3.

Finishing the Clay in Preparation for Molding

Once the final touches have been made to the original clay

sculpture, the final procedure before molding is touching up delicate

details and smoothing the surface of the clay to perfection. This

is quite important because any error or imperfection in the clay

would be copied in the molding process and would appear in every

subsequent stage. Thus, the smoother the clay, the less work will

be needed on the wax replica and the finished bronze casting itself.

Hook tools, or rake tools, are often used to cut the clay down to

a new contour and to leave small raised ridges on the surface. For

smoother surfaces, rubber or metal kidney tools can be used. For

really fine surfaces, a brush and a solvent are used to whisk away

all tool marks.

Once the desired smoothness has been achieved, the piece should

be allowed to dry thoroughly before continuing to the molding process.

|

| 4.

Making a Mold of the Clay Original

When the clay sculpture is completely smooth and finalized,

a mold must be made of the original clay. Excellent surface replication

of the original can be achieved with a polyurethane mold compound

or a high-quality silicon rubber.

The most common material used to produce a mold today is a material

known as Smooth On. It is a latex rubber that is very carefully

formulated to be able to pick up the minutest details in a work.

The rubber mixture is applied directly to the surface of the clay,

using a brush to actually “paint” it onto the surface.

Special attention needs to be given to avoidance of air bubbles

that may be trapped within the rubber mixture.

Once the first coat of rubber has been applied to the surface, it

must be allowed to thoroughly dry (usually for 24 hours) before

the next coat is applied. All of the details from the original clay

are now picked up within the rubber material that has been painted

on. A mold most generally consists of three to five coats of rubber

(applied over the course of several days).

Once the final coat of rubber has dried, a firm outer "jacket"

is made to help retain the shape of the more flexible rubber mold

for pouring the wax replica. This “jacket” is usually

made out of plaster, Hydrocal, resin, or epoxy, and is called the

“mother mold”.

When all of this is complete and it is all dry, the outer "jacket"

is removed, and the rubber is then cut away from the clay, on what

is called a parting line (simply the division line for the mold).

The sculpture has now gone from a positive form to a negative form.

If the sculpture is large or complex, it will usually have to be

divided into smaller pieces, with each piece needing its own individual

mold. The pieces will be rejoined later, after the sculpture is

cast in bronze, to make the complete sculpture whole again.

The learning process for making an excellent multiple piece rubber

mold can take years. A novice should hire a professional, or make

a plaster waste-mold of the original and make a plaster cast (a

positive). From this solid positive a rubber mold can be made without

risk of "losing" the original. The highest quality mold

will save much time and money in production.

|

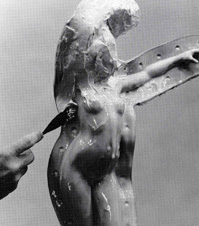

|

Above:

Sculptor Tuck Langland

applies the first coat of rubber by brush to make the mold of his

sculpture "Dawn".

Above:

Sculptor Tuck Langland

applies the third coat of rubber by spatula.

Above:

Sculptor Tuck Langland

applies the top plaster "jacket", or "mother mold",

to hold the form of the mold. |

A

worker pours melted wax into the "mother mold" through a

hole in order to make a wax positive. |

|

5.

Pouring a Wax Replica From the Mold

With the “mother mold” complete, positive forms can

now be generated by pouring a wax replica. Pouring a wax is usually

done in four stages or coats. The first coat is applied by heating

the wax to a temperature of approximately 220 degrees Fahrenheit.

While the wax is quite hot, the mold is rotated about, in an attempt

to coat the entire internal surface of the mold with the melted

liquid wax, which is poured into the “mother mold” through

a hole. The second coat of wax is applied slightly cooler, at around

200 degrees. The final two coats go on at approximately 180 to 185

degrees.

A

completed wax should be approximately 1/4” thick, or just

slightly thinner. When the wax cools and the mold is removed, a

wax positive of the sculpture emerges.

If the sculpture is a bas relief, or if it has a large mold that

opens wide, it is usually much easier to brush on the wax. Following

the same temperature guidelines per coat as above, the wax must

be brushed on beginning in the deepest hollows of the mold to avoid

any drips.

|

| 6.

Wax Chasing

"Wax chasing" is the procedure of repairing all

of the imperfections that were created during the pouring process

of the wax to maintain the original details within the mold. There

will most always be a few air bubbles, seams, and mold lines which

will need to be removed from the surface of the wax positive.

"Wax chasing" is usually performed at the foundry by a

professional "wax chaser". However, if the sculptor prefers,

they can do the "wax chasing" themselves.

The "wax chasing" procedure is done with small, delicate

tools for scraping, and with a hot tool for filling in the imperfections

within the wax. Once the wax is back to a perfectly finished state,

the sculptor inspects the wax. If the wax receives the sculptor's

approval, it is ready to go to the foundry for spruing.

|

|

A

wax chaser at Schaefer Foundry in Arlington, TX, works on the wax

with small tools to remove any imperfections. Photograph by Elizabeth

Loggins. |

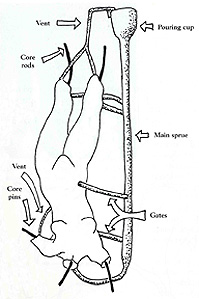

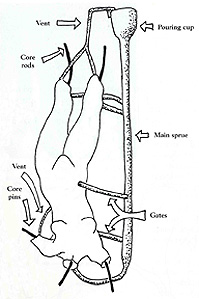

A

diagram of the sprue system by Sculptor Tuck

Langland. |

|

7.

Spruing a Wax

The finished wax is a positive replica of the original clay. A network

of wax rods, called sprues and gates, are next attached to the positive

wax model. These sprues will serve as a type of channel system,

which will feed the molten metal to all of the areas of the sculpture,

as well as allow gases and air to escape. Also, a wax funnel (called

a pouring cup) is attached to the gates for use during pouring.

|

|

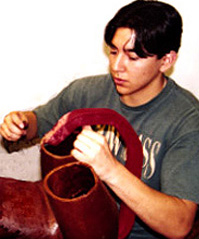

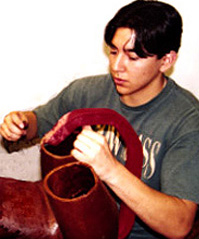

A

worker at Schaefer Foundry in Arlington, TX, attaches a sprue system

to a wax portion. Photograph by Elizabeth Loggins. |

During the spruing process, special care is given to areas such

as the tips of a rabbit ear, or the fingers of a frog, to ensure

that these fine areas will not “short pour”. Once the

spruing is completed, the wax is ready to go on to the shelling

process.

|

| 8.

Ceramic Shell (Investment Casting)

The ceramic shell process requires a series of dipping the wax positive

into a mixture called slurry to create a hard shell. This ceramic

shell, once dry, becomes a hard, durable shell around the entire

sculpture that is going to receive, hold, and shape the molten metal

to produce the bronze figure.

The wax is first dipped into a solvent, which cleans any loose particles

or debris from the surface of the wax. The shell process is about

to begin. The clean wax is dipped into a solution called prewet,

followed by two coats of a very fine grained slurry. This is known

as the primary coating. This is where all of the fine detailing

in the piece is picked up. It is almost like grained silicon flour.

The shell then progresses through the slurry process, into different

slurry mixtures, which are various grades, gradually becoming courser

with each coating. Each time the wax is coated with the ceramic

slurry mixture, it is allowed to dry thoroughly. Each coat adds

support to the overall strength of the shell. The ceramic shell

process consists of seven to nine coats of slurry mixture. Once

all of the coats have dried, the ceramic shell is then sent to be

“dewaxed”.

|

| 9.

Melting/Burning Out the Wax

When the ceramic shell is complete, it is placed in a high

pressure sealed oven, known as an autoclave. High temperatures (1500

to 1800 degrees Fahrenheit) and pressure force the wax from the

shell and the wax melts out, thus becoming "lost". This

is where the name “Lost-Wax Process” has been derived.

The wax has now left the shell, leaving the detailed impression

within the shell, which will soon become filled with the molten

bronze. This step also hardens the ceramic shell in order to prepare

the shell for the extreme temperature of the molten bronze which

it is about to receive.

|

The

workers at Schaefer Foundry in Arlington, TX, carefully lift up the

crucible, containing the molten bronze, out of its heating furnace.

Photograph by Elizabeth Loggins. |

|

10.

Casting/Pouring the Bronze

When the ceramic shell is empty of wax, it is then re-fired and

made ready to have the molten bronze poured into it. All of the

hot ceramic shells are taken to the pouring floor, where they are

either placed in sand to stand by themselves, or they are wired

to a support frame to be held in place.

The solid blocks of bronze, meanwhile, are heated to a temperature

of approximately 2250 degrees Fahrenheit so that liquid bronze is

created. The liquid bronze is stirred and prepared for the pour.

|

| When

the molten bronze is ready, the foundry workers very carefully lift

the crucible, containing the liquid bronze, out of its heating furnace.

The workers must wear protective face shields, clothing, gloves,

and boots.

Moving quickly and very precisely, the foundry workers pour the

liquid bronze into each awaiting ceramic shell. When the ceramic

shells are all full with the poured bronze, they are then left to

cool for several hours. The negative space within the ceramic shells

have now become positive bronze castings.

|

|

Right:

A worker at Schaefer Foundry in Arlington, TX, pours the molten bronze

into ceramic shells. Photograph by Elizabeth Loggins.

|

|

|

Sculptor

Tuck Langland breaks

apart a cooled shell to separate the metal inside from the shell. |

|

11.

Break Out

Once the bronze and ceramic shell has cooled, the ceramic

shell is broken off to separate the bronze metal from the shell.

This is done with hammers, tools, power tools, and sand blasters.

This process needs to be done very cautiously, though, in order

not to cause unwarranted damage to the metal surface. Once the entire

ceramic shell has been removed, the sprues (which have now become

metal) must also be cut away or sawed off.

At this stage, the uncovered bronze is considered a "raw metal".

|

| 12.

Metal Chasing

"Metal chasing" is the process of finishing the metal

back to the appearance of the original. This process usually involves

a fair amount of welding with a high frequency welder. Grinders

are often used to remove sprues. Angle grinders with a variety of

different grades of Roloc pads are used to finish the surface of

the bronze. Always start out with a courser pad and then work your

way down to a very fine pad when chasing the metal.

It may also be necessary to retexture some areas of the bronze.

This can be done with a tool known as a pencil grinder. This tool

uses a variety of high-speed burrs, some of which are quite similar

to those used by a dentist, to perfect the final bronze.

|

|

A

metal chaser at Schaefer Foundry in Arlington, TX, works on the metal

with small tools to remove any imperfections in the final bronze.

Photograph by Elizabeth Loggins. |

| 13.

Metal Welding/Assembly

If the sculpture being created was rather large or complicated,

it might have been cut into pieces during the mold stage. This is

necessary in order to be able to make molds that would be small

enough to pour bronze into evenly. That is, instead of one big mold

for a large piece, the piece may have been broken up into five or

ten different smaller pieces, each piece with its own mold. Each

smaller mold would thus be a different part of the whole sculpture,

so that when all of the pieces have been poured and chased, they

can then be fit back together to create the whole piece.

If this is the case, all of the separate bronze pieces must be welded

together to create the whole sculpture again. A metal welder will

use a high frequency welding torch to carefully weld the sculpture

together. After the sculpture is welded back to one piece, all of

the weld lines must also be chased away so that they disappear and

it looks as though the sculpture was all one piece to begin with.

|

|

A

welder at Schaefer Foundry in Arlington, TX, carefully welds a bronze

bird to a branch. The bird's wings need to be added as well. Photograph

by Elizabeth Loggins. |

A

worker at Schaefer Foundry in Arlington, TX, uses the sand-blasting

cabinet. Photograph by Elizabeth Loggins. |

|

14.

Sand-Blasting the Bronze

When the final piece is all welded together and chased to perfection,

the bronze is next sand-blasted (or bead-blasted) to make it very

smooth and shiny. Using a sand-blast cabinet is the most convenient

way to sand-blast a sculpture. The sculpture is placed inside of

the cabinet and the lid is closed securely. A worker can insert

their arms into the cabinet through holes on the side of the cabinet

which have gloves attached to protect the worker's arms. Wearing

these protective gloves, the worker can then operate the sand-blasting

compressor while monitoring the progress through a window in the

cabinet.

After the sculpture is sand-blasted, the sculptor once again inspects

the piece for accuracy. Now that the bronze has been sand-blasted,

its true gold-like color, almost like glowing platinum, is visible.

The sand-blasting also makes the surface of the bronze more porous,

allowing the top surface to be more open to penetration of the patina

in the next stage.

|

| 15.

Patinazation

The "patina" is the color of the bronze. "Patinazation"

is the process whereby a calculated chemical reaction between bronze,

acidic chemicals, and high temperatures oxidize the surface of the

metals. Certain chemicals will produce certain predictable colors

when they are sprayed on the bronze and then heated up.

The patina process begins by heating (usually with a torch) the

surface of the bronze to a temperature of approximately 450 to 475

degrees Fahrenheit. The surface will have a nice golden appearance

when it is ready. A wide variety of techniques can then be used

for chemical application, the most common being done with natural

bristle brushes. Chemicals can also be applied with spatter guns,

spray bottles, and airbrushes.

|

|

J.D.

uses a blow torch to heat a bronze in preparation to apply the patina.

Photograph by Elizabeth Loggins. |

The

bare metal, before the patina is applied, of "Head of Dawn"

by Sculptor Tuck Langland.

"Head

of Dawn" by Sculptor Tuck

Langland after the final patina is applied (with ferric nitrate

over liver of sulfur). |

|

The

chemicals applied to the bronze will interact with the metal, creating

a colored or textured appearance to the surface of the bronze. The

patina has become quite an art in itself, and many beautiful combinations

can be achieved.

Browns, golds, and reds are typically produced through the use of

Ferric Nitrate. Greens and blues can be produced with Cupric Nitrate.

Whites and beiges can be produced with Bismuth Nitrate and Zinc

Nitrate. Silver Nitrate is very expensive, but if applied very hot

and with persistence and expertise, it can create a beautiful silvery-gray

patina.

The ancient Asians would bury their bronzes to naturally oxidize

them, sometimes for years, in order to create patinas. Today, the

oxidation and coloring of bronze sculpture can take place within

a matter of hours. But it is still a delicate process that should

be performed with caution and with the proper equipment, preferably

by a trained patineur.

After

the patina is applied, the patineur and the sculptor decide between

two sealants to protect the patina. The traditional method of protection

is to apply several thin coats of clear paste wax to the surface,

which is then lightly buffed with a soft, clean, cotton cloth. This

patina should last indefinitely indoors. However, if people repeatedly

touch certain areas, the bronze may be expected to eventually shine

through.

Because today's outdoor atmosphere is more corrosive and carries

a higher content of manmade pollutants, a more durable lacquer,

metal protectant is recommended for any sculptures placed outdoors.

Incralac™ is one such sealant designed specifically for copper

and its alloys. Since Incralac™ produces a plastic-looking,

high-gloss finish, the sculpture must be waxed to create the soft

look of a traditional patina.

|

| 16.

Completion: The Finished Sculpture

After the completion of all of the above steps, a unique bronze

sculpture will have been produced and can now be sold. Of course,

if this piece sells and the sculptor wants to make another one,

that sculptor will then have to return to the “mother mold”

and go through all of the steps again in order to make another bronze

sculpture.

One of the main things to keep in mind when viewing sculpture is

that the "lost wax" process creates truly unique sculptures.

Although the sculptors examine each of the waxes, and double check

each finished metal, due to the handmade nature of this process,

each cast and each patina will be similar but still distinctively

unique.

|

|

Right:

The finished sculpture "Kenyan Dancer" by Sculptor Tuck

Langland. |

|

|

|

|

Left:

"From Clay to Bronze: A Studio Guide to Figurative Sculpture"

by Sculptor Tuck Langland. |

|

17.

Summary: The Lost-Wax Process

Volumes have been written on the subject of the "lost-wax"

process as well as the procedures of mold-making, casting, and patinazation.

We hope you have found this overview of the "lost-wax"

process interesting and enlightening.

For further information about the art of the “lost-wax”

process, Sculptureworks recommends the book From Clay to Bronze:

A Studio Guide to Figurative Sculpture (pictured at left) by

Sculptor Tuck Langland,

one of our Sculptureworks artists.

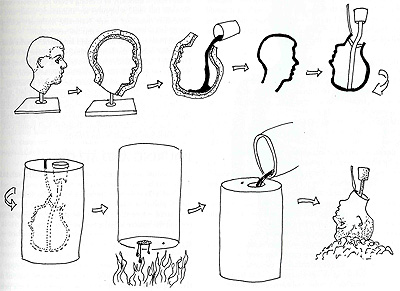

Also, the below diagram from Tuck's book gives a visual summary

of the complex "lost-wax" process.

|

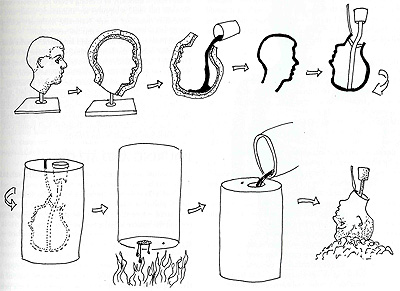

Right:

Diagram by Sculptor Tuck

Langland showing a summary of the “lost-wax” process

(from clay to bronze) with solid, or traditional, investment.

Top row, left to right: the original clay sculpture, the rubber

mold with shell (or "mother mold"), pouring wax into the

mold, the hollow wax cast, and adding the sprue system.

Bottom row, left to right: the wax with investment, burning out

the wax, pouring the bronze, and breaking the cast.

|

|

The

above diagram is found in Sculptor Tuck

Langland's book "From Clay to Bronze: A Studio Guide to Figurative

Sculpture".

|

|

The "lost-wax" process explained above is primarily used

for casting sculptures in bronze. Other options, however, for casting

sculpture include bonded bronze, bonded marble, and pewter. Bonded

bronze (AKA "cold-cast" bronze) is primarily resin. The

surface is a skin of resin into which bronze powder has been blended.

Bonded marble is resin with marble powder. With a low-luster white

surface, it is subtle and quite beautiful. Bonded bronze and bonded

marble are hand-cast, hand-finished, lighter-weight and less-expensive

alternatives to bronze. Pewter, an alloy of nickel and silver, is

another less-costly alternative.

Also, if you are interested in creating a sculpture using the "lost-wax"

process, it is important to note that shrinkage will occur in any

casting process. The mold shrinks. The wax shrinks. The metal shrinks.

A sculpture which in clay was 26" long may be 25" long

in metal.

|

|

18. Care for Bronze Sculpture

All bronze sculpture is an investment which must be properly cared

for.

For

indoor bronzes, the bronze should be wiped with a clean, soft rag

once a year. Use a soft brush and apply a coat of Johnson's Paste

Wax or Tree Wax to the sculpture. Allow it to sit for an hour or

so and then buff it with a soft brush or rag. This will protect

your bronze from the oil of human hands, dust, and grease.

Outdoor bronzes should be treated twice a year by cleaning and waxing

the metal. Generally, this cleaning should be performed right before

and right after summer. Waxing the bronze right before summer is

especially important because this will protect it during the hot

summer months.

|

|

|

|

|